Armenians in Canada: A glance at the past, a vision of the future

My goal in this work is to share some thoughts and concerns and to raise awareness and perhaps start a conversation.¹

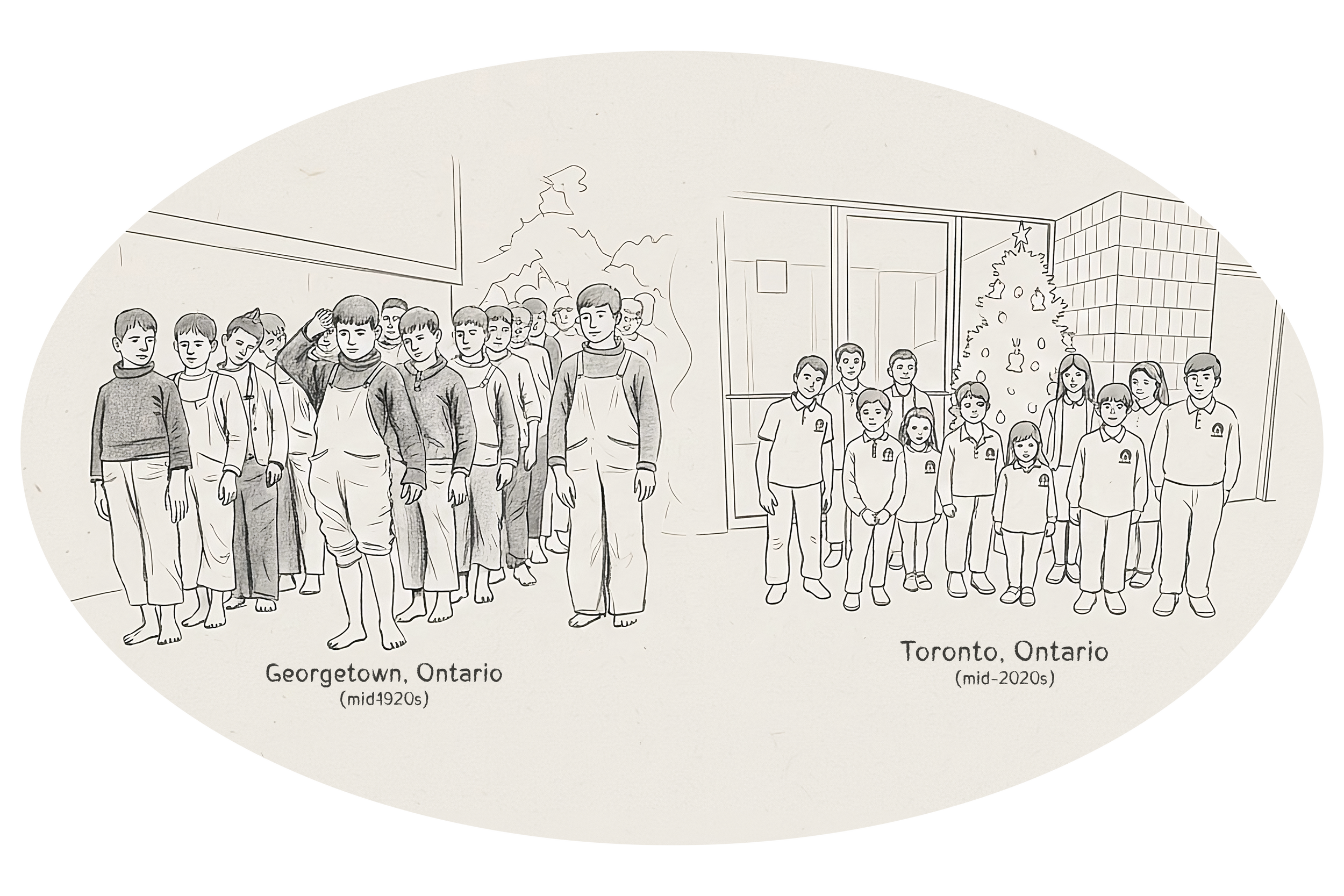

This image was created using Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Background ²

As background to my piece, let me give a brief overview of how Armenian Canadians in Toronto and Montreal have entrenched their identity. To begin with, they have built churches and those of different denominations: Evangelical, Pentecostal, Catholic, and Apostolic under the jurisdiction of both the Diocese and Prelacy. Political, cultural, charitable, social, and sports organizations bolster community participation. Social aid services provide assistance for individuals and families. Scouts for the young and seniors’ groups for the elderly expand the scope of participation. As an example, the Toronto Roubina chapter of the Armenian Relief Society (ARS) has recently organized a group, named the Golden Circle, to provide women over the age of 65 with intellectual stimulation, physical exercise, and culinary delights. Armenians have their cafes and restaurants, pharmacies, and various business enterprises, as well as weekly and monthly newspapers and television shows. They have members in every profession and elected representatives in parliaments. Most importantly, they have constructed full-time elementary and secondary schools. Indeed, the Toronto and Montreal Armenian Canadian communities have created what the distinguished Canadian sociologist, Raymond Breton, has called institutional completeness.

Looking back over the last 100 years of Armenian settlement in Canada, we see a notable and, one might add, a disturbing pattern which I describe in the paragraphs below.

Although a handful of rug merchants had started businesses in Toronto before World War I (1914-18), the first real Armenian settlement in the city did not get underway until the 1920s, with the entry of about 100 refugee men and women, all survivors of the Genocide. During the same period, Hamilton had about 240 Armenians, and St. Catharines could boast an Armenian population of about 310, composed of recent refugees and pre-1914 immigrants. Meanwhile, Montreal had just a few Armenians, among them, Yervant Pastermadjian and Kerop Bedoukian, both involved in the rug trade and both later leaders in the Canadian Armenian Congress (CAC).

A relatively small number of immigrants entered Canada during the Depression years of the 1930s and the war years in the early 1940s. By the early 1950s, the Toronto Armenian community had begun to wither somewhat, through old age, natural attrition, and intermarriage. Nevertheless, the first Armenian church in Toronto, Holy Trinity, was erected in the early 1950s, due largely to the participation and support of the 1920s’ refugee settlers, in cooperation with the rug merchants.

During the early part of the 20th century, the number of Armenians in Canada grew very slowl,y primarily because their entry had been more or less blocked by Canadian officials who had classified them as Asians, therefore undesirable, and therefore unwelcome.

Armenians in the United States also suffered immigration discrimination. The U.S. government claimed they were not white, therefore ineligible for naturalization. If successful, this claim would have revoked the citizenship of hundreds of Armenians already naturalized in the U.S. In United States v. Carozian (1925), the Armenians won a landmark victory that confirmed their classification as white and therefore eligible for U.S. citizenship.

No such court case was pursued in Canada, where government authorities stubbornly and unwaveringly rejected the many Armenian initiatives to have the Asian designation removed.

During the 1960s, immigration restrictions began to be lifted on a broad scale. The attitude of government officials and politicians towards Armenian entry improved somewhat, aided by the lobbying efforts of the Canadian Armenian Congress. Easing restrictions on Armenian entry led to the blossoming of the Armenian communities in Montreal and Toronto, which became the principal targets of Armenian settlement. Concurrently, as conditions in Middle Eastern countries deteriorated and grew increasingly more dangerous, Armenians sought the safety of Canada. These push-and-pull factors played out over the next many decades, indeed, up to the present day.

With each movement, the newcomers brought their exuberance and vigour and rejuvenated the existing community. The latest flow has been from Syria. Syrian Armenians are pure dynamism and have reinvigorated Armenian community life. Such newcomers have been vital–a godsend really – to retaining Armenian ethnocultural identity, maintaining Armenian communal survival, and continuing to inspire a truly Armenian spirit in Canada.

Yet there is cause for anxiety and disquiet. Depending on immigration movements to sustain Armenian existence as a viable minority raises disturbing issues. What, we must ask, became the role of the previous immigrant generation, notably their children born in Canada and their grandchildren? Are these generations still part of the ethnocultural community? Are they involved and do they participate in the world of their parents and grandparents? In other words, how does one define the status of the Armenian Canadian community as we move further away from the immigrant cohort?

Within this framework, let us explore two areas: Community structure and family formation.

Community structure

To examine community development over a long period of time, I undertook a demographic study of the Armenian community in the city of Hamilton, 35 miles west of Toronto.³

In the 1940s, about 60 Armenian families lived in Hamilton. They had 126 children, of whom 13 never married. Forty-nine of the 126 children married Armenians. Of those 49, 19 moved away from Hamilton, usually to join their out-of-town partners, leaving 30 endogamous couples in the city, with spouses from both inside and outside Hamilton.

Of the 126 children, 64 married non-Armenians, and of those, 18 left the cit,y and 46 remained in Hamilton. Thus, we are dealing with 30 endogamous marriages and 46 exogamous marriages of individuals, many of whom were first-generation children of Genocide survivors.

In a way, the Hamilton community was confronted with a fork in the road. One path was to remain pure but small with those 30 endogamous couples, thus foreshadowing potential extinction. The other option was to incorporate the 46 mixed marriage couples into the community to enlarge it, but also to risk diluting it. No official decision emerged one way or another. It simply evolved that the mixed marriage couples were more or less marginalized. Either they distanced themselves from the community voluntarily, or they felt they were sidelined by community members.

A friend of mine in Hamilton serves as an example. She had been an active member of the Armenian Youth Federation (AYF); and her mother was a devoted member of the ARS. My friend married a non-Armenian and they had two sons. After some time, we seldom saw them at Armenian functions, not even at picnics. If we had asked her why, she would have replied, “It’s too hard on my husband. He doesn’t know Armenian, and no one ever talks to him.” Frankly, I doubt if anyone ever approached him with a welcoming invitation: “Hey, Gary, it’s great to see you here among us. How are things? A group of us is going golfing next week. Would you care to join us?” An odar⁴ he was and an outsider he remained. Unfortunately, his wife and 2 sons also stayed away.

In Western society, the further we move from the immigrant generation, the more likely we are to encounter exogamy, especially in a small group like the Armenians. It seems to me that Armenians must accept the fact that exogamy is inevitable. If this is the case, then Armenians, as a community, as a small community, must deal with it consciously and conscientiously. Please note, I am not advocating one kind of marriage or another. I am simply stating facts. How can or should Armenians cope with increasing exogamy? It is not an insurmountable problem. They need to extend a hand to mixed marriage couples and their children and welcome them into their midst. They need to incorporate them into their community, help them feel they belong, and let them know they are a member of the community. Incorporation and connectedness play a formidable foundational role in Armenian ethnocultural survival. Indeed, incorporation stands side by side with immigration, because it is fundamentally unrealistic for Armenians to rely on immigration alone for their survival in the diaspora, nor should they depend on immigration indefinitely.

One may criticize this approach as being self-serving. I suppose to a degree it is. By way of argument, however, let us look at another perspective that deserves some thought. In our North American society, it is crucial to belong to something. Family, of course, but also to a group. We must never underestimate communal power and the role of community in our lives. We must have friends to share our joy, comfort us in our sorrow, and help us in our time of need. In a world dominated by social media, our institutions and organizations offer human contact, linguistic opportunities, and generous support.

The friend I mentioned above grew old, like the rest of us. Her husband died. Her sons placed her in a nursing home. Who visited this lonely woman? Who took her a bowl of pilaf? Who held her hand and reminisced about “the good old days”? Who eased her pain with the Hayr Mer? Who even knew where she had been placed? Then, one sad day, we read her obituary. These words in her death notice are etched in my memory: “She was proud of her Armenian heritage.” Let us never undervalue the depth of communal belonging and the bonds of human love and respect.

Family formation

We now move on to family formation as part of our survival mechanism. Statistics Canada states that Canada’s population replacement or fertility rate is 2.1 children per woman of child-bearing age, roughly from 15 to 44 years old. The actual birth rate in Canada for 2023 was 1.26, considered among the lowest in the world–similar to Italy, Spain, South Korea, and Japan.

Unfortunately, there is no way of easily calculating the fertility rate of Armenian Canadians from census data. Based on my observations and interviews with various community members, I estimate the birth rate among Armenians in Toronto today is approximately 1.5-1.6, slightly higher than the national average in Canada but much lower than the replacement rate of 2.1.

This finding is deeply worrisome.

Such a low birth rate spells trouble for Armenian ethnocultural survival, for I doubt the Toronto community is alone in experiencing such a problem. If this trend continues, the ethnocultural community will be up against a potential population catastrophe. Indeed, this finding foreshadows doom for the Armenian diasporan future, unless community leaders, mindful of the fragile situation, spread awareness of the replacement shortfall and take steps to help reverse it.

Reverse it, they must. But how?

Simply by encouraging the creation of larger families.

Churches and schools are important. But in the end, they are only bricks and mortar. Armenians need to hear the prayers of their people rising up in their churches and the voices of their children ringing in their schools. Armenians need more Armenians.

I am not recommending that every Armenian family have eight children. Nor am I suggesting we interfere in the personal and private decisions of couples about their priorities and family planning. Nor do I wish to make couples feel guilty or unpatriotic for choosing to have small families. Obviously, the final decision is theirs. The job of the community, notably the leaders in our organizations and institutions, is to inform the people, to raise awareness of this urgent dilemma, and to motivate a change in outlook and attitude.

Such an initiative must be a basic component of Armenian community life. It does, indeed, take a village to raise a child, especially in these difficult economic times. Luckily, the “Armenian village” of Toronto possesses the intellectual capacity and financial resources to back up young families. Consider, for example, the school. “Villagers” provide scholarships for the students; and the school gives special consideration to families who have enrolled more than two children.

In short, the community as a whole, but in particular the community leadership must not only promote the concept of larger families, but they must also undertake to help those families, especially those with working mothers, including young professional women.

Conclusion

Armenians are a small ethnocultural group in the diaspora, numbering about 80,000 in Canada. If they vanish from this diaspora, and they are without question vulnerable, it will be largely by their own doing. To a certain extent, Armenians are masters of their own fate.

Certainly, the Armenian Canadian leadership is aware of the precarious condition of the community. Accordingly, the formation of organizations and institutions is vital to the health and sustainability of community life. But organizations and institutions need people. Here is where the landscape of survival requires a palette of three vibrant colours:

Immigration. To a degree, Armenians in Canada are dependent for survival on the movement of Armenians from other diasporas. In Hamilton, the 30 endogamous families mentioned above would long since have vanished had it not been for the entry of Armenians during the 1960s. Today, while Hamilton is struggling with a church and a community centre, it is, nevertheless, surviving. It goes without saying that the influx of Armenians to Canada weakens other diasporas. However, if such diasporas are endangered because of political and military strife, then emigration is the only sensible alternative.

Intermarriage Incorporation. The incorporation of mixed marriage families into the community with the full force of welcome is absolutely essential to Armenian survival. If Armenians open their world to odars, they will surely build up their community strength and ensure longevity.

Larger families. Such an initiative should be embedded in the Armenian Canadian communal psyche. The added imperative that the children grow up as Armenian Canadians should be guaranteed by the community leadership and full community participation.

In these many ways, Armenians can reinforce their community and give hope for future survival. If they want their great-grandchildren to identify themselves as Armenian Canadians, then Armenians, as individuals and Armenians as a group, must make concerted, deliberate, and determined efforts to take on a measure of control over their own destiny, for their own survival. ֎

Notes:

1. This article is a revised version of my presentation to the Armenian Bar Association Annual Conference held in Toronto on June 14, 2025.

2. Professor Kaprielian-Churchill was recently honoured by the National Executive of the Armenian Relief Society (ARS) of Canada with the first Artsakh Award for her contributions to Armenian Canadian scholarship.

3. For this study, I rely on a mailing list of Armenians in Hamilton during this period and on my memory of a time and place where I was born and grew up. Given the length of time that has elapsed and the fallacy of memory, I recognize that my numbers may not be 100 per cent accurate. However, I stand by the correctness of my general findings.

4. Non-Armenian

This essay was published in Torontohye's Dec. 2025 issue (#220).