Reflections on Ara Baliozian: The case for supporting English-language Armenian writers

Ara Baliozian marched into my parents’ kitchen and ripped the painting of Mount Ararat, proudly hung above the dining table, into shreds.

Obviously, that did not literally happen. But I couldn’t help but feel attacked when I read the opening lines of one of his books, which warned the reader that they “will not find in here any lamentation after the fact or chauvinist nonsense about the eternal snows of Mount Ararat.” Chauvinist nonsense? Who was this guy to tell me that pining after a major cultural symbol–a symbol that represented our displacement from the Armenian highlands–was chauvinist nonsense?

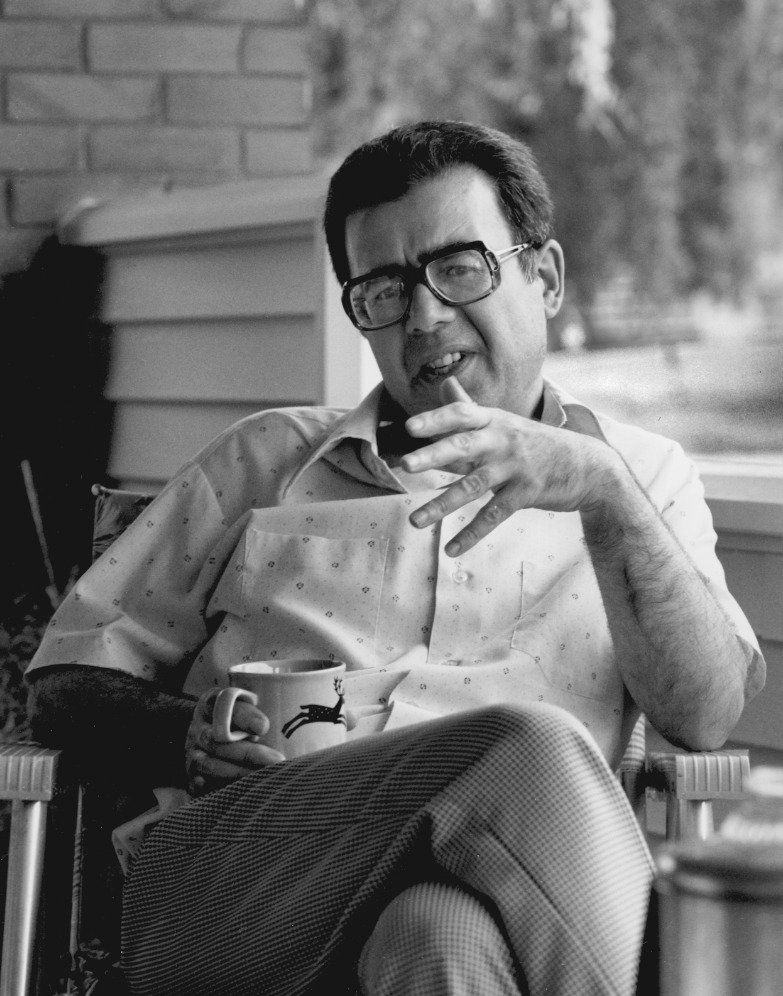

If you are not familiar with Baliozian, be warned that many of his books would come with a trigger warning today. Baliozian was born in Greece to Armenian Genocide survivors and went on to be educated in Italy. He later immigrated to Canada and spent most of his life right here in Southern Ontario. Throughout his decades-long career as a writer, he published many books, including English translations of Armenian writers like Zabel Yessayan, Krikor Zohrab, and Gostan Zarian. However, his true claim to fame lies in his critiques of Armenian institutions and culture. Due to his contrarian nature, he was often ostracized and attacked by other Armenians. He later distanced himself from the Armenian community and is now retired from writing.

Ara Baliozian marched into my parents’ kitchen and ripped the painting of Mount Ararat, proudly hung above the dining table, into shreds.

Ara Baliozian marched into my parents’ kitchen and ripped the painting of Mount Ararat, proudly hung above the dining table, into shreds.

It is disappointing to see a writer of Baliozian’s calibre fade into obscurity. His books are out of print and hard to find in mainstream marketplaces. You can scrounge up bits of old interviews and blog posts on the internet, but nothing substantial. Baliozian is so disconnected from our community consciousness that a few years back, there were widespread rumours he passed away. At the time of writing, these rumours remain untrue.

Photo: Ara Baliozian by Kaloust Babian

I had my first chance encounter with Baliozian’s books in high school. At that point in my life, I was not a regular at the local Armenian community centre, and there was no chance of me being introduced to Armenian writers in traditional Armenian schools, community libraries, or community group settings. I was also oblivious to the Toronto Reference Library’s small collection of Baliozian’s books. These books were not available for loaning out anyway, meaning I would have to travel over an hour on public transit to read them.

The first book I read by Baliozian was Unpopular Opinions, which I found in my mother’s collection of books. The book is a compilation of various short essays and articles he wrote throughout the 1990s, criticizing the Armenian community’s approach to free speech, democracy, and education. He argues against repeating the same cliches and dogmas about our history and culture, and instead embracing a sense of pluralism, allowing for a diverse range of beliefs and ideas to shape our community practices. While Baliozian is a big supporter of the intellectual tradition of the Armenian writers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, he also takes inspiration from 'odar' (non-Armenian) philosophers and ideas. The result is a thought-provoking collection of writing that challenges readers to question deeply ingrained beliefs and encourages open-mindedness. He urges Armenians to move beyond mere nostalgia and to critically engage with their traditions and history, advocating for a community that values inclusion, critical thinking, diversity of thought, and a commitment to progress.

Baliozian’s arguments are rooted in a genuine desire to see the Armenian community evolve and thrive in a modern, global context. In my opinion, he accurately diagnosed how divisions along partisan, religious, and other lines cause Armenians to behave as a collection of ‘tribes’ rather than a united nation. These tribes, separated from working with others with their shared goal, are more susceptible to becoming limiting echo chambers and driving community members into assimilation.

Baliozian’s books are not for the faint of heart. I was initially taken aback by his brash and blunt style, but I grew to find it necessary. A good cultural commentator does not coddle egos. You should feel a deep sense of conviction and call to accountability when reading meaningful work. Baliozian did that for me.

Upon spotting my tabbed and abused copy of Unpopular Opinions, an older community member was surprised that I was reading his work. They were a fan of his writing back when he would still attend events. Beyond being able to meet Baliozian in person, they had experienced, first-hand, the events and version of the Armenian community in the late 20th century to which Baliozian was responding.

In comparison, my relationship with Baliozian and the events he responded to remain purely parasocial. Still, his work remains relevant today, and because of that, I am able to relate to him and his ideas.

The chapter in Unpopular Opinions I related the most to was the one on “time-frame theorists,” who Baliozian claimed were “a dime a dozen among us.” Time-frame theorists are those who blindly believe that it is the mere passing of time that will cure the social ills of the Armenian community. Common sentiments expressed include: it will take two to three generations to produce honest leaders; it will take another 20 years to have social progress; it will be the new ‘golden generation’ that renounces old limiting mentalities. The solution to corruption, lack of inclusion, lack of social progress, reckless materialism, and any other societal issue is not the action of implementing education, regulation, positive social pressure or other active measure - waiting it out is sufficient.

When put in those terms, the “time-frame theorist” mentality is clearly delusional. However, it is not uncommon to see it propagated when it is politically convenient. I felt deeply convicted when reading this because I had been surrounded by ‘time-frame theorist’ mentalities and had allowed it to influence how I viewed social progress in the Armenian community. Baliozian made me accountable to my contributions to Armenian social progress. I still ask myself: What am I doing to support positive change in the Armenian spaces I frequent? How am I working to include all ‘tribes’ of Armenians? Baliozian repeatedly emphasizes that he criticizes Armenian institutions so that they can be reformed for the better rather than boycotted unequivocally and subject to attrition.

Baliozian’s books are not for the faint of heart.

Baliozian’s books are not for the faint of heart.

Now, I am not saying that I (or any other Armenian) is individually responsible for resolving all social issues present in the Armenian community. I appreciate that Baliozian, as a critic, discusses community members’ contributions to progress in proportion with their perceived power to enact reforms. Baliozian does not demand anything beyond my abilities as a minor player in the community; I am fully capable of forming a nuanced understanding of my culture and history, and working to bring that open-minded perspective to my interactions with community members.

Baliozian is also a critic who knows his place. He lived in the diaspora for all of his life, so his writing focused on his lived Armenian experience–he primarily focuses his critique on diasporans, not those in the modern Republic of Armenia. Baliozian unambiguously separates the homeland and diaspora, going so far as to say when asked about diaspora-homeland policy disagreements in an interview: “The homeland and the diaspora have different priorities. It would be selfish of us to assert our priorities are superior or more urgent than the homeland’s. Live and let live.” Again, this is another Baliozian snippet that struck a nerve: How can he say that to diasporans like me, who, if anything, want to be more invested in the affairs of the homeland?

I began to understand this quote when I visited Armenia this past summer and met with the High Commissioner of Diaspora Affairs. I had asked them what work was often misassumed to be their responsibility, and the answer was surprising: As part of restructuring during recent years, the responsibility of providing Armenian educational material to diasporan institutions was redelegated. It is no longer the Office of the High Commissioner that deals with diasporan Armenian education. I was told that the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture, and Sports (MoESCS) is now supposed to deal with requests for educational support. Obviously, this is not an ideal result: The MoESCS is preoccupied with a number of much more pressing and relevant issues (improving the rankings of Armenian post-secondary institutions, modernizing education curriculum and school infrastructure, etc.). An Armenian Saturday school in Boston that wants more children’s books about Armenian history falls low on the priority list for them, however, diasporan Armenian children’s education as a bulwark against assimilation is likely a top three issue in the diaspora.

The homeland and the diaspora often have different priorities, as Baliozian said, and it’s not an issue so long as each has its own strong, accountable institutions to deliver those priorities independently. It’s important to note that Baliozian does not minimize the diaspora’s role in aiding the homeland. In another interview, he says, “The Azeris have oil on their side; we have our diaspora.” However, it is to be expected that two groups with two different experiences of Armenian life have different issues to contend with. And each understands its issues best.

I was initially taken aback by his brash and blunt style, but I grew to find it necessary.

I was initially taken aback by his brash and blunt style, but I grew to find it necessary.

I am disappointed that despite his insights, Baliozian is not more mainstream. Baliozian’s limited reach is expected, though, as he is an Armenian writer with a limited target audience. He writes in English and for Armenians familiar with North American Armenian community dynamics and seeking commentary and critique on said dynamics. His themes are incredibly ethnocentric. A lot of English-language Armenian cultural products are created with a foreign audience in mind these days and are, therefore, limited in the scope of cultural analysis they can perform. Suppose you are creating something for an ignorant audience. In that case, you have to start at the building blocks: the history of the Armenian Genocide, basic geopolitics, stereotypical fun facts about food and art. When you’re spoon-feeding information from a level of zero cultural understanding, you will likely never progress to the nuanced analysis needed to grow intellectually. Cultural products in the Armenian language can safely assume a level of cultural literacy that most English-language Armenian content creators do not - except Ara Baliozian.

I would never give any beginner to ‘Armenianism’ a copy of Baliozian’s Definitions: A Critical Companion to Armenian History and Culture. The book is filled with tongue-in-cheek and catty definitions that only someone culturally literate in intra-community diasporan struggles would appreciate (see ‘second-class citizen’, defined as ‘almost any Armenian in the eyes of another Armenian’). It is also not a book that flatters the Armenian community: It is not propaganda about being the first Christian nation, winning sports matches, or being prominent or famous. The definitions in the book are not what I want non-Armenians to know as the first thing about being Armenian; they are for Armenians to read by ourselves. It is not a book upon which we should base our entire self-image, but Armenians who are secure in their identity can definitely stomach a few lines of sarcastic critique.

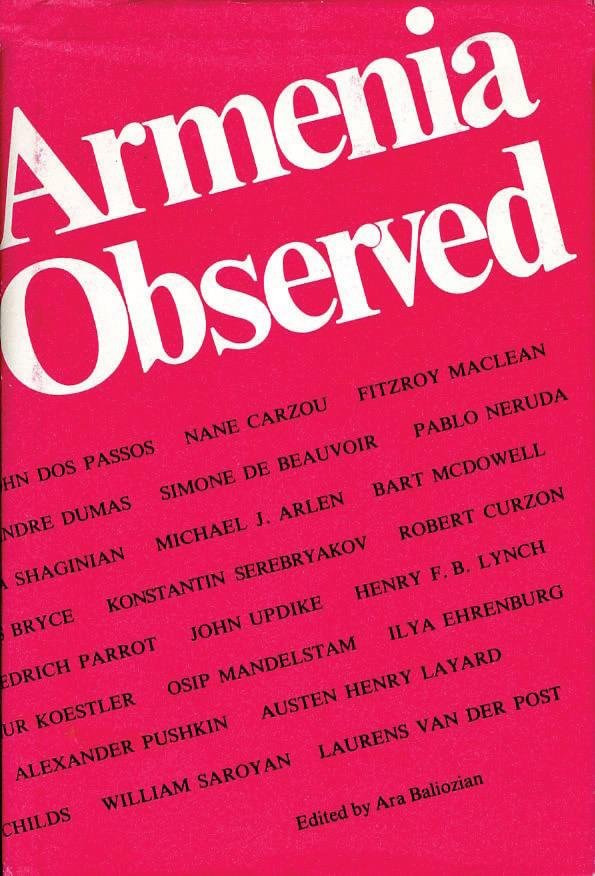

Since we have a growing anglophone diaspora, I believe it is essential to meet their intellectual needs by stimulating English-language content on Armenian history, culture, and society that doesn’t resort to cliches. When I read 'Armenia Observed,' a book Baliozian compiled and edited of various travelers' reflections on visiting Armenia, I understood that the lived experience of being Armenian contributes to deeper, high-quality writing. The book features lots of great foreign intellectuals, from Simone de Beauvoir to Alexander Pushkin, repeating the same stereotypical tourist observations: Yerevan as a pink city, Sevan as a cool lake, sparse villages, great mountains. When I compare that limited vision of Armenia to the diversity and depth of perspectives Armenians themselves can offer, I am all the more motivated to support quality Armenian-themed writing.

Baliozian made me understand the need for Armenian writers. He praised the many he translated, but he also set the example himself. ֎

This piece was published in Torontohye's Nov. 2024 issue.