Will you 'Learn for Artsakh'? How a digital library is changing the online conversation around Artsakh

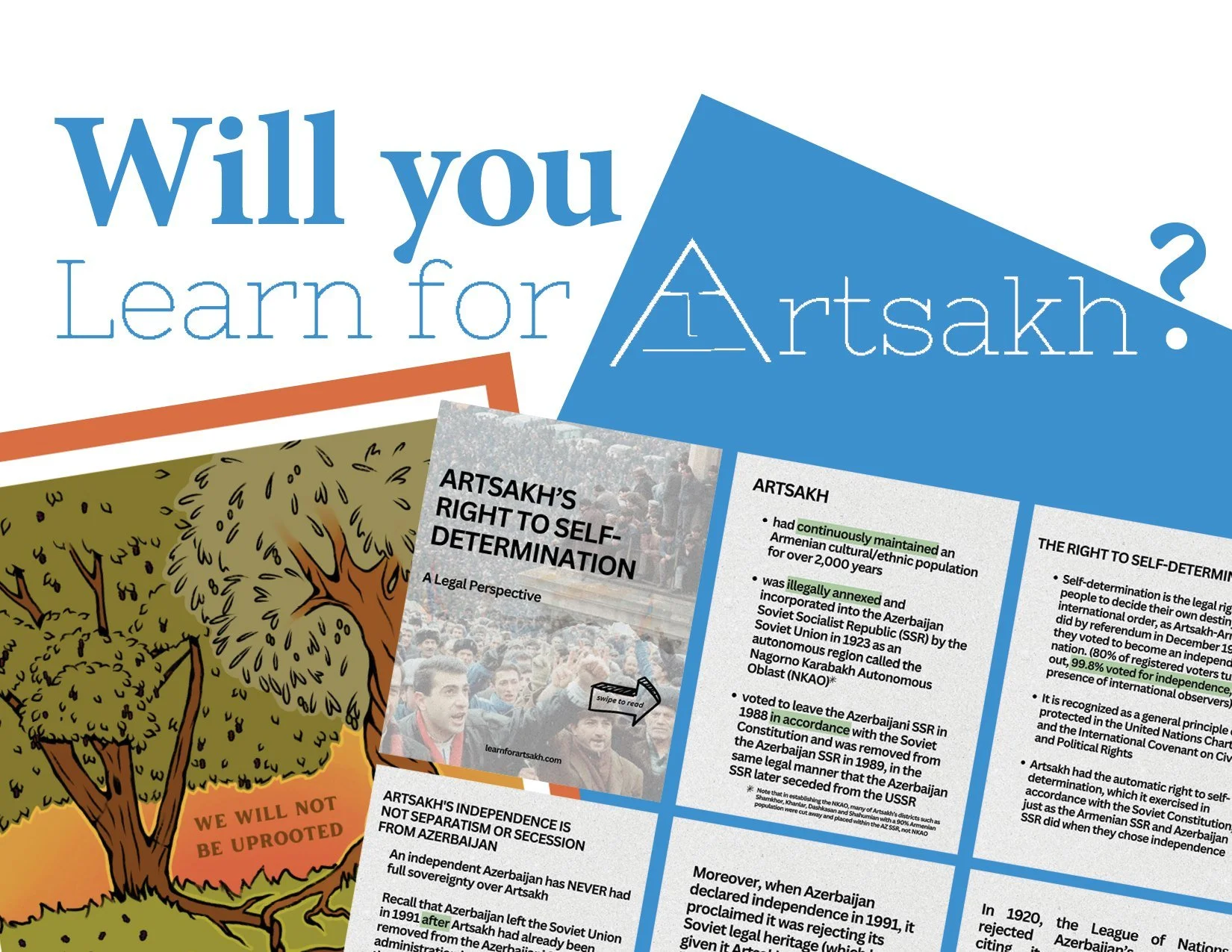

A few months ago, something strange happened in my Instagram feed. Many of my Toronto-Armenian friends had started reposting content from a relatively new account called Learn for Artsakh. The account featured simple infographics promoting support for Armenian issues, such as Artsakh’s right to self-determination, designed to be digestible for Armenians and non-Armenians alike.

As the infographics took over my feed, I realized there was more lurking beneath the surface - the Instagram account was tied to a larger website featuring dozens of free digital books on Armenians and Artsakh. Eager to support this educational initiative, I reached out and had a brief stint volunteering on the site. Despite my limited involvement, I was an instant supporter.

My volunteer work consisted of digitizing the first few sections of “A Report on the Abduction and Torture of Ethnic Armenians” by Physicians for Human Rights. The report details first-hand accounts of Azeri war crimes during the First Artsakh War. The only physical copy of this report is available at the DIGNITY Danish Institute Against Torture’s library, and it can’t be loaned out. The report is also available online in the form of fuzzy photos posted on a poorly maintained website with bad graphics - in short, the vital information it contains exists in a form where no one would easily find it. I began converting this report into a correctly formatted, readable PDF using text recognition software. A few weeks into my work, Learn for Artsakh had already converted the information into shareable infographics. The infographics took over my feed, and suddenly, it seemed thousands of people were empowered by previously hidden and inaccessible knowledge.

The woman behind the initiative chose to be identified only by her first name, Anahit, due to concerns about online trolls. She is a 22-year-old Artsakhsti with roots spanning across Artsakh. Despite moving to the U.S. when she was six, she maintained close ties with her homeland, visiting Stepanakert every summer. Naturally, when the 2020 War started, she was hit very hard emotionally.

“What can I do in diaspora?” she was left asking. “My heart is pulling me towards Artsakh, but I feel so helpless.” She had noticed a gap in the online information space; there were very few accessible books about Artsakh, actually written by Armenians.

Many who were seeking to be educated about the Armenian cause were being referred to Western writers like Thomas de Waal, who Anahit described as “profiting off our pain” and engaging in bothsidesism.

It wasn’t that Armenians hadn’t written about Artsakh–they had written extensively about the Armenian Cause in several languages. However, there were many barriers to accessing those books, including high costs and few copies available outside major Armenian hubs.

Anahit was determined to change this. In 2020, amid full-time university studies, Anahit set out to the Glendale Public Library armed with the suitcase. She borrowed nearly two dozen books on Artsakh and carefully scanned them, creating digital copies. The urgency to get information out overruled concerns over copyright laws. This was the beginning of the Learn for Artsakh digital library.

Anahit had also found old websites made by Armenians about Artsakh, with their own collections of books. These websites were fairly inaccessible–for one, they were primarily written in Armenian or Russian. On top of that, they were old websites, made in the early 2000s, before website builders had gained popularity and made it easy to develop and maintain websites. These websites were only accessible through an internet archive called the Wayback Machine. Luckily, Anahit downloaded approximately 500 books on Artsakh from these sites and set to translate them.

Anahit delayed publishing the site due to her perfectionism. She wanted to have a grand launch for the website, with hundreds of books perfectly digitized and translated, but the 2023 Artsakh Genocide rushed her plans and pushed her to launch the site early.

Despite being published as an ‘incomplete’ site, Learn for Artsakh is a rich resource. The site contains a ‘beginners’ section, intended for those new to the Armenian issues like the 1915 Genocide and the struggle for Artsakh’s self-determination, and an ‘advanced’ section, intended for those seeking to deepen their understanding further. There is also a project recruiting Armenian artists to create new posters and revitalize old ones, and an online dictionary of the Artsakh dialect.

However, in my opinion, the biggest resource on the site is the translations and digital copies of books. These seem to be the most helpful to educators, students, and others seeking to decolonize their perspectives on Artsakh.

While exploring the site's origins, I connected with a local University of Toronto student, Arina, who was involved in translation work for the initiative. While she initially downplayed her contributions, they are worth highlighting.

Arina had been involved in Learn for Artsakh since its early days and was keen to build a popular resource for online organizing spaces, something she hoped would be “politically conscious and aware.” Her initial role began as a researcher, researching Armenian revolutionaries and resistance stories. However, her role within the project later evolved to use her knowledge of Russian.

Arina helped translate a book by Artsakhtsi writer Leonid Karakhanovich Hurunts, titled Alone with Myself or How to Reach You, Descendants! The English translation of this book is currently available on the Learn for Artsakh website. Anahit highly recommends reading it, and it’s easy to see why. The book is a precious primary source on the Artsakh Liberation Movement, written by one of its early founders. Hurunts documents many instances of violence and suppression against Artsakhstis living under Soviet rule that are not frequently discussed, even in mainstream Armenian circles, due to a knowledge gap of Artsakhtsi life during Soviet Azerbaijani rule.

Translating Hurunts’ work was deeply fulfilling for Arina. “I like doing my translating work, " she tells me, explaining that it sharpens her Russian language skills. “I sometimes read the stuff in Russian, and I think, ‘This is so important; this is so educational’. I then think of all the Armenians who aren’t able to read it because they don’t read Russian.”

Arina’s translation work extends beyond just translating books. She and another volunteer, Sonya, recently translated Tsvetana Paskaleva’s 1993 documentary “My Dears, Living and Dead” from Russian to English. This documentary on Operation Ring, the forced deportation of Armenians from the Shahumyan region of Artsakh, is available for free with English subtitles on the Learn for Artsakh website. The 15-minute documentary is part of a series of seven documentaries by Paskaleva, a Bulgarian-Armenian journalist who documented the First Artsakh War to draw attention to the gross human rights violations. Paskaleva went on to present her documentaries to the UN, Amnesty International, the Canadian Parliament, and the US Congress.

While Learn for Artsakh recruits all kinds of volunteers, including people purely involved in digitizing, like I was, translators seem to be the most essential. Anyone with knowledge of English and another in-demand language (Armenian, Russian, Turkish, Arabic, French, German, Spanish, Georgian) can contribute. Both Anahit and Arina emphasized the flexible environment translators work in, translating a little bit of content at a time.

The initiative was founded as a way for diasporans to contribute from a distance, and the volunteers’ accomplishments are something to be proud of. “There are Armenian stories that need to be told,” says Arina, describing her motivation to join the project. “You do this work for yourself and your community.”

For those looking to support without the time commitment of volunteering, Anahit and Arina recommend taking the time to read and educate yourself using the available resources and to share them online. Anahit recommends that those new to Artsakh issues read The Caucasian Knot - while the book is not perfect, it provides a good backgrounder to the Artsakh cause. Arina recommended Monte Melkonian’s The Right to Struggle, a book that ties the Armenian cause with other transnational solidarity movements.

Of course, for those truly short on time, the Learn for Artsakh Instagram account manages to dole out detailed information in a digestible, short format. The crowd favourite is an infographic called “A Legal Perspective on Artsakh’s Self-Determination”, which is a great shareable resource. The information shared empowers Armenians and allies to stand firm against the torrent of misinformation caviar diplomacy has brought into legal spaces.

Overall, it is difficult to walk away from the Learn for Artsakh digital library unimpressed. Despite online hate, Anahit and the volunteers march on, making Armenian texts accessible to Armenians and non-Armenians alike. Their efforts contribute to a broader effort to platform Armenian, especially Artsakhtsi, stories. To paraphrase a sentiment in my conversations with both Anahit and Arina: “When there’s a targeted campaign to deny your existence, education becomes a form of resistance.” ֍

This article was published in Torontohye’s Aug. 2024 (#204) issue.